JavaScript OOP Performance Shootout

2020 December 04

In a previous post I compared a couple of approaches to OOP object creation in Javascript and compared the pros and cons of each. One thing I mentioned about the function closure, or factory function, approach is that it would likely perform worse when instantiating a large number of objects. Let’s test it out!

CPU Performance

For each case I’ll be using the class based and function closure based approaches from the previous post, along

with the following test code to create and instantiate many “Person” objects:

Setup code

class PersonC {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

this.energyLevel = 10;

this.sleeping = false;

this._deepestThoughts = "What _do_ snozzberries taste like?";

this._restIntervalId = null;

}

askName() {

if (this.sleeping) return;

return `${this.name} says "Howdy! I'm ${this.name}!"`;

}

askThoughts() {

if (this.sleeping) return;

return `${this.name} ponders the universe, then speaks: "${this._deepestThoughts}"`;

}

exercise(exertionLevel) {

if (this.sleeping) return;

this.energyLevel = this.energyLevel - exertionLevel

if (this.energyLevel <= 0) {

this._sleep();

}

}

_rest() {

this.energyLevel = this.energyLevel + 1;

if (this.energyLevel > 5) {

this._wake();

}

}

_sleep() {

this.sleeping = true;

this._restIntervalId = setInterval(this._rest.bind(this), 1000);

}

_wake() {

this.sleeping = false;

clearInterval(this._rest);

}

}

function PersonF(name) {

let energyLevel = 10;

let sleeping = false;

let _deepestThoughts = "What _do_ snozzberries taste like?";

let _restIntervalId = null;

function askName() {

if (sleeping) return;

return `${name} says "Howdy! I'm ${name}!"`;

}

function askThoughts() {

if (sleeping) return;

return `${name} ponders the universe, then speaks: "${_deepestThoughts}"`;

}

function exercise(exertionLevel) {

if (sleeping) return;

energyLevel = energyLevel - exertionLevel

if (energyLevel <= 0) {

_sleep();

}

}

function _rest() {

energyLevel = energyLevel + 1;

if (energyLevel > 5) {

_wake();

}

}

function _sleep() {

sleeping = true;

_restIntervalId = setInterval(_rest, 1000);

}

function _wake() {

sleeping = false;

clearInterval(_restIntervalId);

}

return {

sleeping,

askName,

askThoughts,

exercise,

}

}Class based instantiation

var people = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

people.push(new PersonC(`Neo${i}`))

}

for (var i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

people[i].askName();

people[i].askThoughts();

}

return people;Function based instantiation

var people = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

people.push(PersonF(`Neo${i}`))

}

for (var i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

people[i].askName();

people[i].askThoughts();

}

return people;Each of the test cases initializes 10,000 instances of each person object and calls a few methods on the new object. In my local test results on Chromium 92/Ubuntu 20.04 the class based method consistently runs a little over twice as fast.

Instantiation by class x 2,215 ops/sec ±0.55% (64 runs sampled)

Instantiation by function x 980 ops/sec ±0.68% (65 runs sampled)

You can test this live on your current browser with the benchmark button below:

Awaiting test run...

Now for some memory usage tests

The main performance impact I envisioned in my earlier post was that the function closure method of creating objects would lead to more memory usage, due to the enclosed private functions being recreated for each instance of the object, instead of shared like they are for class based objects.

Measuring this programmatically proved a little bit more difficult than measuring CPU times as the APIs to get memory usage are not very granular, and are not approved web standards.

My initial attempt was testing out the Chrome-specific performance.memory

API. The approach here was to simply call performance.memory.usedJSHeapSize before any allocations, after one group of allocations, and

then after the final group of allocations and compare the differences between each. The result of this call showed the memory usage of

10,000 class based objects to be a grand total of 0B, while the total of 10,000 function closure based objects ended up in the 5MB range.

Clearly this was incorrect, and given the non-standard status of the API I decided to abandon this approach.

I briefly looked into another similar Measure Memory API which is still in the unofficial draft phase, and implemented in Chromium based browsers only. However the goal of this API seems to be more geared towards total page memory usage and not designed for the granular type of memory measurement that I was after.

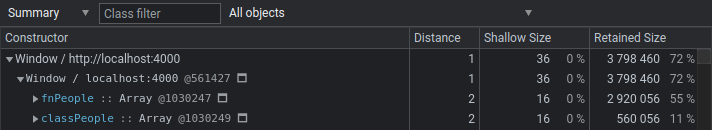

As a fallback, even though it isn’t programmatic, I decided to use the built in heap snapshot tooling of the Chromium dev tools. This should at least give a rough idea of how closely the two object instantiation methods compare in terms of memory usage. [Note from the future, this gives a very exact view of the memory usage of each of these methods!]

For the tests, I allocated 10,000 of each object type and collected them into an Array slapped right onto window using the

button below.

The following is the result of the heap profiler in Chromium 92/Ubuntu 20.04:

I ran this snapshot multiple times, across multiple page loads and all results were very similar, showing the function closure approach to retain approximately 5-6x more memory than regular classes, given the object structures defined above!

Let’s dive a little deeper into where the memory is taken up for each of these objects:

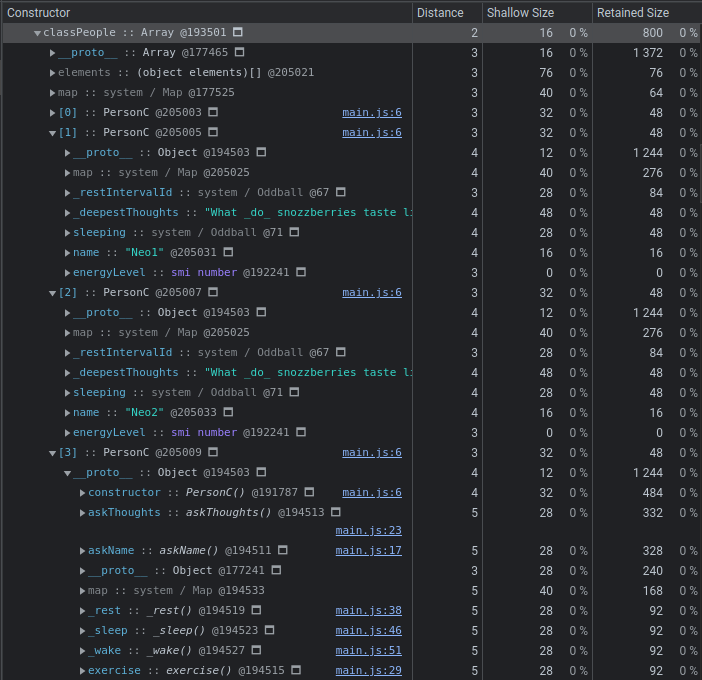

Class based memory usage

In the above heap snapshot of an array of class based PersonCs we can see that each instance uses just 48B of memory

in the Retained Size column. Which pieces of

the PersonC object are unique to each object, and will be freed when the object is garbage collected and which pieces are shared?

We can see in each of the expanded objects that each object references the same prototype object (via memory reference @194503), and in the third

expanded object we can see that this prototype is built using the PersonC() constructor. This constructor function takes up 1,244B of memory and contains

all of the instance methods defined in the class, shared among each instance. We can also see the _restIntervalId and sleeping properties

that share memory across instances (“Oddball” values encompass undefined, null, true and false). The map :: system value here is an

internal property used to enable fast property lookup in JavaScript objects, which is also shared. The _deepestThoughts value, since it is statically defined for

all instances, is an interned string while energyLevel is a small integer number, both of which also share memory across instances of the class.

Taking all these into account, the only pieces of memory that are unique to each object, at least without mutation of their internal values, are

the name property (16B), which is a different string for each object, and the memory needed to store information about the object itself (32B), for

a total of 48B per object.

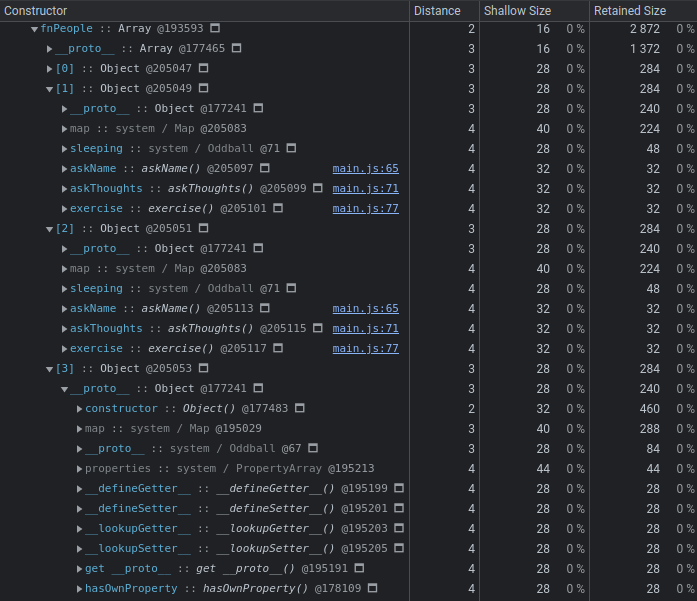

Function closure based memory usage

In the function closure based method of object creation we can see that each object consumes 284B of memory compared to the 48B of the class

based equivalent. We can also see that each instance here shares the same prototype object, but expanding the prototype shows a constructor

of type Object() - the base of the prototype hierarchy in JavaScript. Since all objects in JavaScript tie back to this original

prototype, the garbage collection of PersonF based objects will not free any of this memory. At the top level of each object we can

find references to the askName, askThoughts and exercise functions (each 32B), and see that each one is a separate instance

due to the different memory addresses.

As an aside, further proof of shared memory can be seen in the browser console:

window.classPeople[0].askThoughts === window.classPeople[1].askThoughts

> true

window.fnPeople[0].askThoughts === window.fnPeople[1].askThoughts

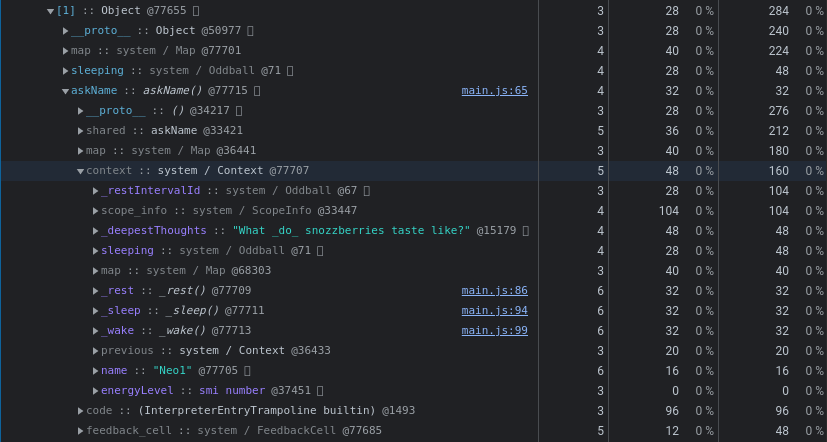

> falseThis leaves quite a bit of retained memory, and a bunch of properties, unaccounted for. Where are the other functions and values defined

in our PersonF function? Digging into some of the properties we do see reveals a little more. Opening up the askName method shows a menu item

called “context”, and opening that reveals the missing data: the values captured via function closure in askName’s lexical scope.

Totalling up the values unique to the object in the closure scope, _rest, _sleep, _wake and name gives us an additional 112B, bringing

the total to 208B. Then add the memory allocated for each unique object (28B Shallow Size), and the memory for each unique context (48B Shallow

Size) completes the grand total of 284B.

Note that if you were to open each function attached to the Person object you would see a context entry

under each function with the same memory location. However if you were to do the same on another instance in the array you would find that the context value

of the closure has yet another memory location. This because each context is a shared reference to the enclosed values that are created on

every individual call to PersonF(), providing true encapsulation (at the expense of much higher memory usage).

Closing Thoughts

Although there are certainly strong benefits to using function closures for object creation, reducing the chances of programmer error and allowing true encapsulation of data and private methods, this approach clearly pays a penalty in performance and memory usage.

It seems that the function closure approach would be better suited to situations where there are a known low number of objects being initialized, such as the outer boundaries of your application when creating coordinating modules of code. When the number of objects is going to be large, possibly with many properties, or has a need to be initialized very quickly in a loop, the class based approach or even non-OOP approach may be a more appropriate choice.